David examines one of the owls. (Photo by Rachel Karlov)

David examines one of the owls. (Photo by Rachel Karlov)

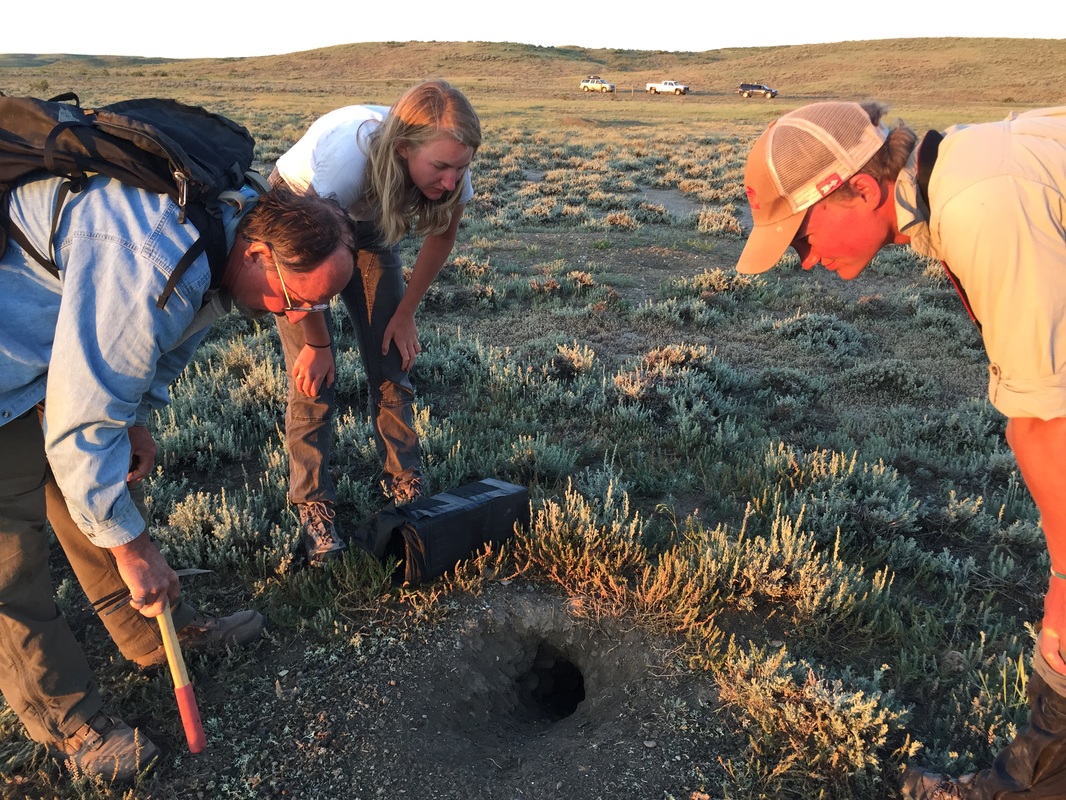

ASC Landmark Volunteer

David Johnson stands hunched over an unsuspecting burrow using the butt of his trowel as a pointer to tell us why he suspects this particular one belongs to a burrowing owl. The wildlife scientist explains that telltale signs include owl pellets, small pieces of scattered skeletons, evidence of previous meals like the cricket leg we saw, and owl droppings, which are called whitewash. Owl whitewash is chalky and has a lower water content, making it pretty easy to differentiate from other bird droppings on the prairie.

The goal of our late-night trip to nearby prairie dog towns is not the kind of work that had occupied the earlier part of our week—this time, owl trapping is on the agenda. Gracie, Brady and I are set to shadow and help David as he set traps in the burrows and, if we’re lucky, wait with him until they fly in. With David’s 40 years of owl experience, we definitely feel we are in good hands.

The first step is to visit each burrow that David and his assistant Annabelle had scouted earlier in the day. We gather all the bits of bone and pellets we can find and set them aside for later. Then David uses the trowel to create a depression at the opening of the burrow where the trap will be set. Once the trap is in place, it’s covered back up with dirt to create a natural appearance and a dirt patio is created. The bits of bone are then scattered back on floor of the trap door entrance to lend to a homey feel.

The most important part of the whole operation is the MP3 player and speakers. The speakers, which are placed inside the burrow at the opposite end of the trap, are responsible for playing the call of a competing male. This three-second call played on repeat serves as both the mating call and the call to establish territory. Wherever a male owl happens to be flying around, it’s going to want to investigate the rival male that has invaded its territory, trying to steal his mate.

Rachel holds her first burrowing owl. (Photo courtesy of Rachel Karlov)

Rachel holds her first burrowing owl. (Photo courtesy of Rachel Karlov)

Finally, the time comes to check the traps. Everything goes according to plan and we catch both a male and a female! Peering into the trap, four big, round yellow eyes follow our every move. David expertly reaches into the trap and grabs one by its legs. It stays much calmer than I would have thought.

He places a leg band on the bird, measures its tail feather, weighs it on a scale, and then hands it us. Needless to say, I am stoked. To properly hold the owl, I place its legs between my thumb and pointer finger and cradle it between my arm and body.

After taking pictures we release both owls back into their burrow and head out to join Annabelle and her crew.

Following a great day of hiking 12 miles for our work with Landmark and swimming in Fourchette Bay, this was the cherry on top. Gracie, Brady and I end the evening with legs dangling off of a tailgate, dust swirling all around us, wishing the moment would never end—and looking forward to the midnight spaghetti and meatball dinner that awaits us.