Tomas Ward has collected field data for conservation biology projects throughout the U.S. since 2004. Oregon, Southeast Alaska, and the Great Lakes bioregion are among the places where he has collected data in the field but working in the Great Plains is a new experience for him. Tomas makes a living as a horticulturalist, builder, and cook and is working with ASC as a Landmark crew member this winter while taking a break from The Organic Gardener in Highland Park, IL.

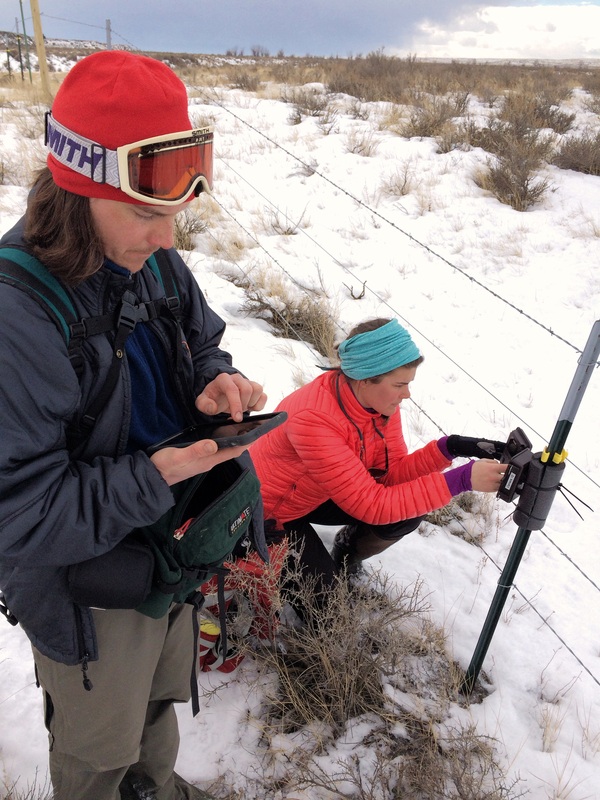

Tomas and Colleen, who make up the Landmark 2 team – or “Dueces Wild” – walk a transect across the prairie. Photo by Jordan Holsinger.

From Tomas:

February 1st, 2014

For the past ten days I have been situated at the Lazy J ranch on the prairie of northeastern Montana, between the Missouri River and the Canadian border. I am here as a volunteer adventure scientist for Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC) doing wildlife monitoring on a privately held natural habitat refuge. The nonprofit that holds title and leases to this land is

American Prairie Reserve, and their goal is to create a 3.5 million acre parcel of continuous land that can support thriving populations of the plants and animals that were present here at the time of the arrival of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

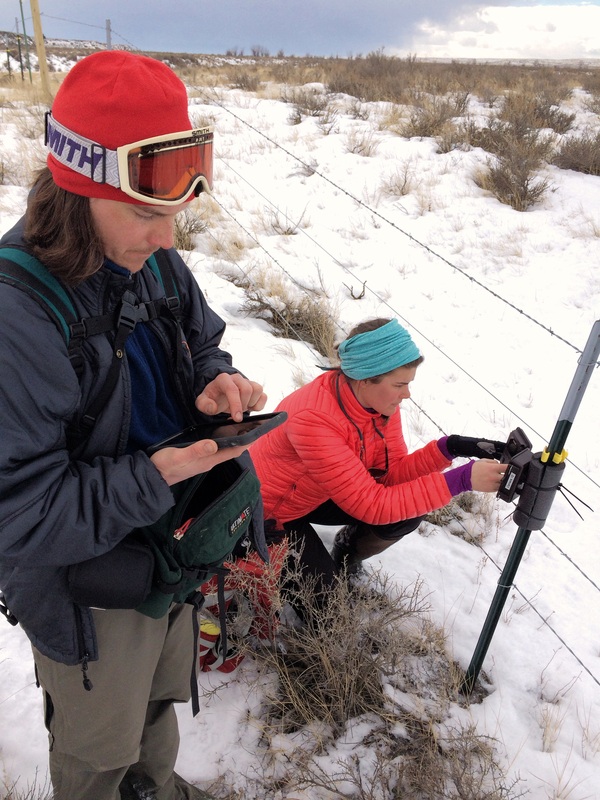

I have agreed to serve on this project until the first of March. The commitment seems daunting at certain moments of the day. The climate of this country is harsh year round, and the winter is not altogether inviting. I drove out here with my brother through the plains of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas, and we were lucky to have temperatures hovering near the freezing point. The ten day forecast that I read today calls for daily highs not exceeding the single digits Fahrenheit and unceasing subzero windchills. Our responsibility as volunteers is to hike out onto the grassland, deploying motion-triggered video cameras to capture wildlife activity and to record observations of animals as we walk. My standard ensemble for this task includes insulated pants, down jacket, heavy gloves, and ski goggles.

Dueces Wild checking one of the many remote camera stations established across the reserve. Photo by Jordan Holsinger.

This week I have been living and working with another Land

mark crew member, an outdoor adventurer named Rob from New Jersey who currently resides in Bozeman, MT. We see a lot of each other, and enjoy such pastimes as fretting together when the tires of our SUV crack through thin ice on stream crossings and sink into the water below. We also have the opportunity to clamber up flood-carved alluvial streambanks, sorting the marble, petrified wood, and igneous rocks that are incongruously jumbled together by ancient glacial expansion. The other folks that we typically see are Damien and Lars, two resident Reserve staffers. On Monday we expect our little lodge to be descended on by an octet of fellow volunteers and staff from ASC, the NGO that is partnering with the reserve to monitor wildlife. This will make up our crew for the month. Rob and I are both cautiously looking forward to this large influx of humankind.

Considering the severity of the climate, and the limited social opportunities, I ask myself why I chose to come out and work on this project. Partly it was to get out of my parents’ house for a while. I have a brief layoff from my job in landscape construction north of Chicago, and I wanted to use the time for a travel opportunity. The original vision was that I would go down to the west coast of Mexico and volunteer at a permaculture homestead. Practicing Spanish, hiking the subtropical forest, and eating mangoes picked off the tree were the activities that I had in mind. But when opportunities and companions for that trip were not immediately forthcoming, I made a phone call to my friend Gregg, who I know from work in Alaska, and who directs citizen science efforts worldwide, to ask if he had anything that I could get on board with. “Short answer is yes, dude,” he replied. “We could probably use you for this thing on the prairie.”

The February Landmark crew gathers over breakfast to strategize for the day with ASC Program Director Mike Kautz. Photo by Jordan Holsinger.

Some time later I was pulling up to the ranch lodge that houses us volunteers this winter. Suiting up every day to go pedestrian into the northern plains wind I think maybe I should have worked a little harder on the south of the border angle. But I am also here following the impulse that has taken me to various out of the way places throughout the first part of my adult life. I have often yearned to be in places where I could experience things growing fecund further away from human influence. A year and a half of botany surveys in the temperate rainforest, a season of growing vegetables in the Midwest heartland, stream restoration work in the transmontane desert, nine months on a mom and pop cattle ranch on the Oregon Coast, and two summers in maritime Alaska are some of the intervals I have spent satisfying my need for natural things and solitude. Pursuit of these journeys was something that endowed my life with purpose and joy through the decade of my 20’s and beyond. Now, at the venerable age of 34, I begin to yearn for a stable income and

maybe a regular girlfriend. But I don’t want the lure of wildlands to fade into a memory. I want to keep living experiences with the less governed landscape. That is why I sojourn here to face the frosty windswept prairie and its solitude.

So here I am, trying to be at home on the range. The buffalo really do roam here. Not like they did when the Corps of Discovery estimated that they could walk from horizon to horizon on the backs of bison, and up to 30 million of them lived on this continent. But the Reserve staff is striving to put a healthy population on its deeded and leased acres. One of the pleasures of being here is immersing myself in the natural history of the bison, which have lived an existence in my mind as cartoonish behemoths printed on wooden nickels and various trinkets of Americana. In fact these impressive animals have lived through an epic journey of evolution from swift forest runners of Eurasia to herds of large mammals wandering Siberia, and across the Bering land bridge to join the megafauna of North America. This suite of animal included lions, cheetahs, the fearsome shortfaced bear, and a variety of grazers. As those other large beasts went extinct some 10 millenia ago, only bison, grey wolves, and the fleet pronghorn were left on the plains.

Documenting a bison skull along the transect. Photo by Jordan Holsinger.

Bison may have a future too, to go with their storied past, in spite of the wanton massacre of buffalo that was part and parcel of our Manifest Destiny. The herd on this refuge currently numbers around 300 and features a relatively high level of genetic strength. As part of our orientation Damien explained that most living bison feature genes from domestic cattle, which resulted from hybridization programs aimed at improving the breed and creating a more domestic “beefalo”. Seeking to grow and maintain a population as close to wild as possible, the Reserve has brought in animals from places where herds are more genetically pure like Elk Island National Park in Canada, and even culled resident animals found to have hybrid genes. “That one was a tough call,” says Damien. We often see a winter herd of about 100 cows and calves while driving to and from our transect terminals, but smaller groups of bulls reveal themselves only when we wander the landscape on foot.

But this is not strictly a bison refuge, nor is it a prairie dog reserve or a sagebrush botanical garden. It’s a Great Plains reserve, and the goal is broadly to make room for all variety of specimens that are a part of a healthy community in this biome. A healthy human social component is of paramount importance if this effort is to be successful. Conservationists, ranchers, and the native community are the stakeholders who must coalesce and find a way into the future to heal this land. The prairie landscape and livelihood are mythologized in our national lore. Real people living here are motivated by desire to build the good and noble things in life that this rich but demanding country has to offer.

Find out more about the Landmark project and apply on the Landmark page. Keep up with ASC by subscribing to ASC’s blog, liking us on Facebook and following us on Twitter (@AdventurScience), Instagram (@AdventureScience) and Google+.